One thing is for certain: the advent of ETFs and the democratisation of derivative products have enabled investors to access all sorts of markets at a lower cost and with performances that are often better than those provided by active management. Last year was a perfect illustration of this point, if we consider that there were only very few active managers in the US equity market who beat the S&P 500 (less than 10% according to the Financial Times), which incidentally is one of the most efficient and liquid markets.

Asset allocation: active management is holding its own!

Thursday, 03/02/2017Although passive management still plays an important part in so-called “pure” (or single-asset class) strategies, such as US equities, there is an area where active management is returning to favour since the advent of the financial crisis : asset allocation. What are the reasons for this development?

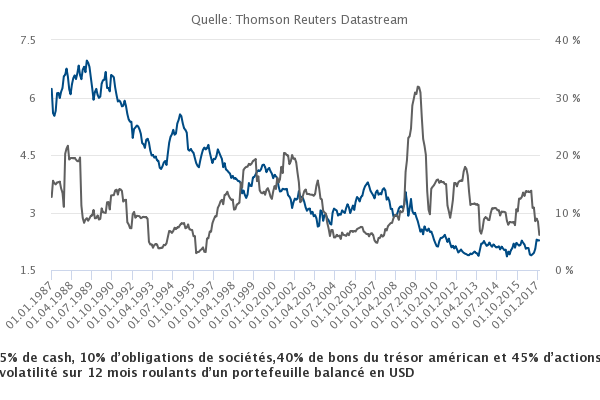

“The drop in the average return on portfolios, combined with the disinflation that we've seen since the end of the 1980s, then the changes in volatility since the TMT bubble burst have sounded the death knell for passive management, or non-conviction-based management, in asset allocation.”

An increasingly efficient market

Risk at the centre of management

Although cost and performance are clearly very important criteria in the choice of management and the financial instruments involved, there is another factor that is just as significant, particularly in asset allocation, namely, risk. In theory, an institutional investor should be a long-term investor, with little sensitivity to market fluctuations in the short term, who relies essentially on their strategic allocation to meet their objectives in the long term. But, as the great Yogi Berra once said, although in theory there is no difference between theory and practice, in practice there is. The financial crisis, the drop in bond yields and aging population have all swung by and returned risk, and its management, to the forefront of the scene. I'm not necessarily talking about the major sovereign funds or the balance sheet of the BNS (although I find it very surprising that there are no drivers for managing risk on a daily basis), but of the majority of pension funds in developed countries. And particularly as their actuarial deficit has increased, “risk-free” rates have slumped and their margin for error has shrunk to nothing. Against this background, excessive volatility or a slump in performances quickly become a major problem.

The end of 50/50 balanced funds

First, this structural trend led to the extinction - or at least to the transformation - of traditional balanced funds, the well-known 50/50 funds (50% equities and 50% bonds). Their expected return declined with the end of the disinflation phenomenon. Some sudden changes in correlation between equities, particularly in 2013 and 2015, did not spare the purely quantitative versions, such as the “risk-parity” funds, either (especially where risk is distributed equally between each asset class). In short, there are no longer any simple “passive” solutions to be found : the lazy option that strategic allocation once represented, in a manner of speaking, has disappeared.

The manager can no longer use the indices as an excuse

So what are the advantages of dynamic allocation, in that case? I can see at least one: the client's objective can be directly reconciled with the work of the manager, free from the tyranny of the indices. Instead of being subject to future performances and volatility according to the arithmetic means of the financial indices, active management allows the client to set evaluated and realistic objectives for performance and volatility in the short and long term. This can be reviewed periodically, with the manager if necessary, based on changes in the markets (and the margin for manoeuvre). For the manager, whose management will have been regulated by investment directives, ensuring that they are in line with predetermined objectives, it's an opportunity, and a requirement, to express their convictions .i.e. know how best to allocate their risk budget since they can no longer hide behind the indices.

Active management is not a game of chance; it requires a great deal of discipline...

This type of management clearly requires a rigorous and consistent investment process in which at least three of the following ingredients appear. Firstly, an economic analysis at a general and a more in-depth level to determine the assets that will achieve the most growth in the current environment. Secondly, an evaluation of all the assets available to estimate each one’s potential. And lastly risk control, to fine-tune management to deal with increasingly frequent market fluctuations - marginal contributions to risk, correlation between assets, etc.

...and a driver who is experienced in giving orders

For example, this disciplined management process allowed us to detect, two major turning points on the markets in 2016, both linked to US economic outlooks and the monetary policy of the Federal Reserve. The first concerned the emerging market debt in February, at a time when valuations on commodities and high-yield bonds had reached extremely low levels. This valuation was later recognised by the market, as soon as the Fed put the brakes on the tightening of its monetary policy. The second turning point was the vote on the European referendum in Great Britain, over the summer. After the result, the markets dropped because of the downturn in expectations that the Fed would increase its interest rates, and the status quo scenario. We felt that we had to take a more prudent approach with regard to the duration of the portfolios and adopt a bias towards cyclical stocks in equities management, with a preference for securities whose valuations could benefit from a recovery in nominal growth and an increase in interest rates, such as banks.

The implementation of management vision is another area in which active management is fundamental. Taking an exposure in European banks via an ETF does not consume the same risk budget, nor have the same asymmetry as implementing this via a call option, for example. This management action is far from being benign but is fundamental in managing multi-asset portfolios with very different risk profiles ; however, it expresses the same idea.

Naturally, as always in finance, there is no guarantee of results but we must at least minimise the setbacks insofar as possible!

Change in return and risk on a balanced portfolio in USD (5% cash, 10% corporate bonds, 40% US treasury bills and 45% US equities).

Disclaimer

This marketing document has been issued by Bank Syz Ltd. It is not intended for distribution to, publication, provision or use by individuals or legal entities that are citizens of or reside in a state, country or jurisdiction in which applicable laws and regulations prohibit its distribution, publication, provision or use. It is not directed to any person or entity to whom it would be illegal to send such marketing material. This document is intended for informational purposes only and should not be construed as an offer, solicitation or recommendation for the subscription, purchase, sale or safekeeping of any security or financial instrument or for the engagement in any other transaction, as the provision of any investment advice or service, or as a contractual document. Nothing in this document constitutes an investment, legal, tax or accounting advice or a representation that any investment or strategy is suitable or appropriate for an investor's particular and individual circumstances, nor does it constitute a personalized investment advice for any investor. This document reflects the information, opinions and comments of Bank Syz Ltd. as of the date of its publication, which are subject to change without notice. The opinions and comments of the authors in this document reflect their current views and may not coincide with those of other Syz Group entities or third parties, which may have reached different conclusions. The market valuations, terms and calculations contained herein are estimates only. The information provided comes from sources deemed reliable, but Bank Syz Ltd. does not guarantee its completeness, accuracy, reliability and actuality. Past performance gives no indication of nor guarantees current or future results. Bank Syz Ltd. accepts no liability for any loss arising from the use of this document. (6)