Last week, Russian gas giant Gazprom shut off its natural gas supply to Poland and Bulgaria, claiming that the two countries were not paying for their gas imports in rubles, as required by Moscow. A few weeks ago, paying for gas in rubles might have seemed like a good deal for buyers: the Russian currency was trading at 120 rubles to the euro, a depreciation of 35% from its highs. But since the low point on March 7, the Russian ruble has seen a dramatic recovery. It is now trading at 77 rubles to the euro, its highest level in two years.

Yet all the sanctions imposed at the beginning of the war are still in place and have become even more severe. So how did the Russians manage to revive their currency? Here are some explanations.

Internal Factors

Unlike other countries that have had to defend their currencies, the Russian central bank is not in a position to intervene in the foreign exchange market because a large part of its reserves have been blocked since the imposition of sanctions. It is true that on February 24, the day the invasion began, the Bank of Russia intervened for the first time in years as part of a series of measures to stabilize the Russian financial system. Governor Elvira Nabiullina said the central bank spent $1 billion that day, and a smaller amount the next day, to try to support the ruble. But since then, the Russian government and central bank have had to implement other measures to defend their currency.

On February 28, the Central Bank of Russia raised its interest rates from 10% to 20%, which was a strong incentive for Russians to keep holding their local currency.

Another strong measure introduced by the government was the order for Russian companies to convert a minimum of 80% of their foreign earnings into rubles. This means that a Russian steelmaker who earns 100 million euros selling steel to a company in Germany must change 80 million of these euros into rubles.

The Kremlin has also issued a decree prohibiting Russian brokers from selling foreign-owned securities. Many foreign investors own shares in Russian companies and government bonds and wanted to sell their holdings following the announcement of the Russian invasion and sanctions. By prohibiting such sales, the government strengthened the stock and bond markets while keeping assets in Russia, which helped stem the fall of the ruble.

Russian citizens themselves were targeted by the government, as the Kremlin banned them from transferring money abroad. The initial ban stipulated that all loans and currency transfers had to be suspended. These restrictions have been relaxed somewhat recently, but transfers are limited to $10,000 per month for individuals until the end of this year.

Another strong move went relatively unnoticed in the Western media: the Bank of Russia resumed gold purchases at a fixed price of 5,000 rubles per gram between March 28 and June 30. This operation allows the Central Bank not only to link the ruble to gold but also to set a floor price for the ruble in dollar terms (since gold is traded in US dollars). The floor price is estimated at about 80 rubles to the dollar (5,000 rubles divided by 62 dollars per gram of gold). This operation raises the possibility of a return to the gold standard for the first time in over a century. Moreover, with the new link between gold and the ruble, a further rise in the ruble could translate into a rise in the price of gold. Remember that since the annexation of Crimea in 2014, Russia, via its Central Bank, has been the country that has purchased the most gold. It now has the fifth largest stockpile in the world.

External factors

One of the reasons for the ruble's appreciation is the weak link in the sanctions that were imposed by the West: natural gas. The sanctions were originally designed to restrict Russia's ability to acquire foreign currency - dollars and euros in particular. But many European countries continue to buy Russian gas because they are dependent on it and because there are not enough alternative suppliers to meet the demand.

In fact, one of the main drivers of the ruble's appreciation is Vladimir Putin's strategy of requiring some buyers of Russian natural gas to pay their gas bills in rubles. Natural gas contracts are usually written in euros or dollars, and the countries that buy this gas - the EU, the United States, Canada, etc. - have few reserves. Forcing these countries to pay in Russian currency will result in ruble purchases in large quantities (it is estimated that the European Union's purchases of Russian natural gas amount to about $1 billion per day). The demand for rubles could explode, pushing the ruble up. It is the anticipation of this rise that has contributed to the rise in the value of the ruble.

The second flaw in the sanctions is the exclusion of sovereign debt. One of the most damaging measures against Russia has been the freezing of its foreign accounts. Russia holds about $640 billion in euros, dollars, yen and other foreign currencies in banks around the world. The sanctions have blocked Russia's access to these assets, except when it comes to paying interest on its sovereign debt. The U.S. Treasury has left a window open for financial intermediaries to process payments for Russia. That window might close soon but it has been a great help to Russia so far. Without it, Russia might have had to raise dollars by selling rubles, which would have put downward pressure on the currency. And if it had not been able to raise these dollars, it would have defaulted, with negative consequences for Russia and the ruble.

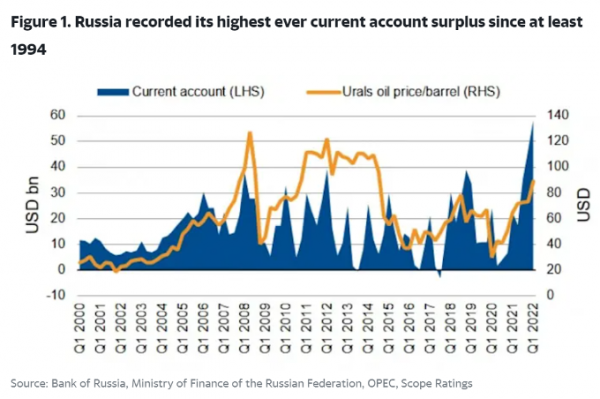

Another factor contributing to the strengthening of the ruble is the increase in oil and natural gas prices. Commodity exporting countries are benefiting from rising prices. This is the case for Russia, one of the world's largest exporters of commodities, which, as we have just explained, continues to export despite the sanctions. In addition to energy exports to Europe, Russia has maintained very strong trade relationships with other major economies such as China and India. The net result is a steady flow of foreign currency into Russia and an explosion in Russia's trade surplus (see chart below).

Is the ruble rebound as real as it seems?

For many analysts, the Russian government has done much more than defend its currency: it is manipulating the ruble market and creating demand that would not otherwise exist.

Some observers blame the Russian central bank for using a variety of tools to make the ruble look like a valuable currency, when in fact very few people outside Russia want to buy a single ruble unless they absolutely have to.

As it is, traders no longer see the ruble as a free trade currency. The capital controls imposed as a result of Western sanctions mean that the exchange rate is effectively managed.

Many exchange offices have even stopped trading the ruble as they believe that the value on the screens is not the price at which it can be traded in the real world.

Russians initially lined up at ATMs across the country to withdraw foreign currency, but the panic has subsided since the ruble stabilized. Strategists say the ruble's rally is not legitimate and that the currency would trade at a very different level if the artificial barriers were removed.

What are the long-term perspectives for the ruble?

The government interventions described above carry significant risks. If Russia succeeds in finding a solution to the Ukrainian problem with the corollary of withdrawing sanctions and restoring trade relations with the West, the ruble can potentially retain its current value. On the other hand, if the measures are withdrawn without a resolution, the ruble could collapse, resulting in an explosion of domestic inflation and a deep economic recession in Russia.

Indeed, some measures - including domestic ones - will have to be withdrawn in the medium term. For example, Russian borrowers cannot continue to pay very high interest rates for long. Interest rates were lowered from 20% to 14% last week, but the absolute level remains relatively high and threatens to stifle industry and growth.

On the other hand, the current account surplus hides the long-term effects of the sanctions, which will inevitably have a strong negative impact on the economy and thus the ruble.

But the biggest threat to the ruble is most certainly the factor that allows it to be so strong at the moment, namely Putin's strategy on natural gas exports to Europe. Gas contracts will eventually have to be renegotiated, and it

is a safe bet that Russia's current customers intend to significantly reduce the amount of Russian natural gas they import. The United States is already sending shipments to Europe. There is talk of supplies from the UK, Norway, Qatar and Azerbaijan. Israel is considering the idea of a gas pipeline. A drop in demand will have a significant negative impact on the balance of trade and de facto the ruble.

Conclusion

After a sharp drop at the start of the war in Ukraine, the Russian ruble has regained much of its value against other world currencies, a change made possible by aggressive capital controls put in place by Moscow and a steady flow of payments for the country's oil and gas exports.

The ruble's resilience in the face of sanctions may allow President Vladimir Putin's regime to claim, at least temporarily, some victory over international efforts to make his government a pariah. However, this improvement in the ruble's fortunes may only be temporary.

Disclaimer

Le présent document a été publié par le Groupe Syz (ci-après dénommé «Syz»). Il n’est pas destiné à être distribué ou utilisé par des personnes physiques ou morales ressortissantes ou résidentes d’un Etat, d’un pays ou d’une juridiction dans lesquels les lois et réglementations en vigueur interdisent sa distribution, sa publication, son émission ou son utilisation. Il appartient aux utilisateurs de vérifier si la Loi les autorise à consulter les informations ci-incluses. Le présent document revêt un caractère purement informatif et ne doit pas être interprété comme une sollicitation ou une offre d’achat ou de vente d’instrument financier quel qu’il soit, ou comme un document contractuel. Les informations qu’il contient ne constituent pas un avis juridique, fiscal ou comptable et peuvent ne pas convenir à tous les investisseurs. Les valorisations de marché, les conditions et les calculs contenus dans le présent document sont des estimations et sont susceptibles de changer sans préavis. Les informations fournies sont réputées fiables. Toutefois, le Groupe Syz ne garantit pas l’exhaustivité ou l’exactitude de ces données. Les performances passées ne sont pas un indicateur des résultats futurs.